While microservices can employ various methods for this purpose, including Single Sign-On (SSO) and third-party services, our discussion will center on integrating a common authentication and authorization framework within microservices. Although there are numerous overlapping patterns with monolithic architectures, microservices demand specific considerations. We will explore these key issues and develop a comprehensive model that enables seamless authentication and authorization across all services in a microservice-based web application.

What is authentication?

Authentication in client-system communication is the process that allows a system to verify the identity of a client, where the client could be a machine, a human, or a human-operated machine interface, and the system is typically a remote application. The client’s identity usually corresponds to a specific user already registered in the system. Therefore, authentication essentially involves confirming whether the requester is indeed the owner of the account from a predefined list of users. This registration process often requires setting up a password or API key, which acts as a shared secret between the user (be it a machine or human) and the system. Thus, authentication fundamentally serves to establish identity, distinct from assigning attributes, roles, or permissions within the system.

What is authorization?

Following the establishment of a user’s identity within the system, it becomes essential to validate their requests based on their authorized rights. These rights can be structured in various forms, such as roles, permissions, or specific constraints to access certain resources within the application. Often, authorization also entails restricting users to their own ‘sandbox’, a common practice in many SaaS applications, where users are limited to interacting only with their resources. Typically, an application will utilize database records to associate users with predefined roles or access rights to certain resources. In a microservices environment, managing these permissions is often handled by a dedicated authorization service, particularly when the business logic necessitates fine-grained access control.

The Basics Of Authentication Logic

User authentication primarily relies on a secret known to both the user and the system. Typically, this involves the user submitting a unique username, often their email, along with a password. The system then verifies whether the username exists in its database and if the provided password matches the stored one. In some cases, an API key is used instead of a password. This key is usually generated following a secure authentication process and serves as a dual representation of the user’s identity and the shared secret between the user and the system. API keys are particularly prevalent in scenarios facilitating machine-to-machine access, as opposed to requests initiated by humans.

In essence, authentication logic is centered on proving a user’s identity for each access request made to the system. This means the client must furnish proof of identity, such as a password or API key, with every request. Consequently, the system cannot inherently link subsequent requests from a client to previous ones as authenticated, even when these requests occur within very short intervals. Therefore, there is no assurance that requests following the initial authenticated one are from the same verified user.

Why Do We Need Tokens?

The concept of tokens emerges as a vital solution in user authentication. Verifying a user’s identity each time they make a request — querying the database, matching password hashes — is resource-intensive for the system. Additionally, repeatedly inputting a username and password for each request can be cumbersome for users. To address these challenges, most systems employ a process where the user’s identity is validated once during the sign-in or login process. Following this, the system generates a token as a more efficient and user-friendly secondary proof of identity. This token, known as an access token, is issued to the user upon their initial access and should be provided with subsequent requests.

Access tokens represent a secure method of storing user data, allowing for its safe storage on the user’s local device. This facilitates automatic transmission of the token with each request, significantly enhancing the user experience. This approach is commonly observed in modern web applications, where users log in once and then continue to interact with the application seamlessly, with the access token managing their authentication in the background.

How Tokens Are Secure?

Tokens have evolved as a secure method of identity verification in software engineering. Initially, tokens were encrypted packets of data containing user information, appearing as a meaningless string of characters to the client side. This encryption ensured that the token data remained unmanipulable. Encrypted tokens encapsulate the client’s identity, issued only after the client provides primary proof of identity (like a password or API key). Since these tokens contain user identity data, any subsequent request accompanied by the token is effectively reasserting the user’s original identity. The foundation of this system is encryption, which acts as a safeguard against data manipulation, thereby ensuring the security and integrity of the authentication process.

The encryption of a token in authentication processes is primarily aimed not at concealing the user’s sensitive information, but rather at ensuring the token’s immutability. This security measure prevents unauthorized individuals from creating counterfeit tokens. By encrypting the token, the system effectively guards against the possibility of external entities simulating token behavior, thus maintaining the integrity and reliability of the authentication process. This approach ensures that only tokens issued by the authenticating system are recognized and trusted, safeguarding against fraudulent attempts to access the system.

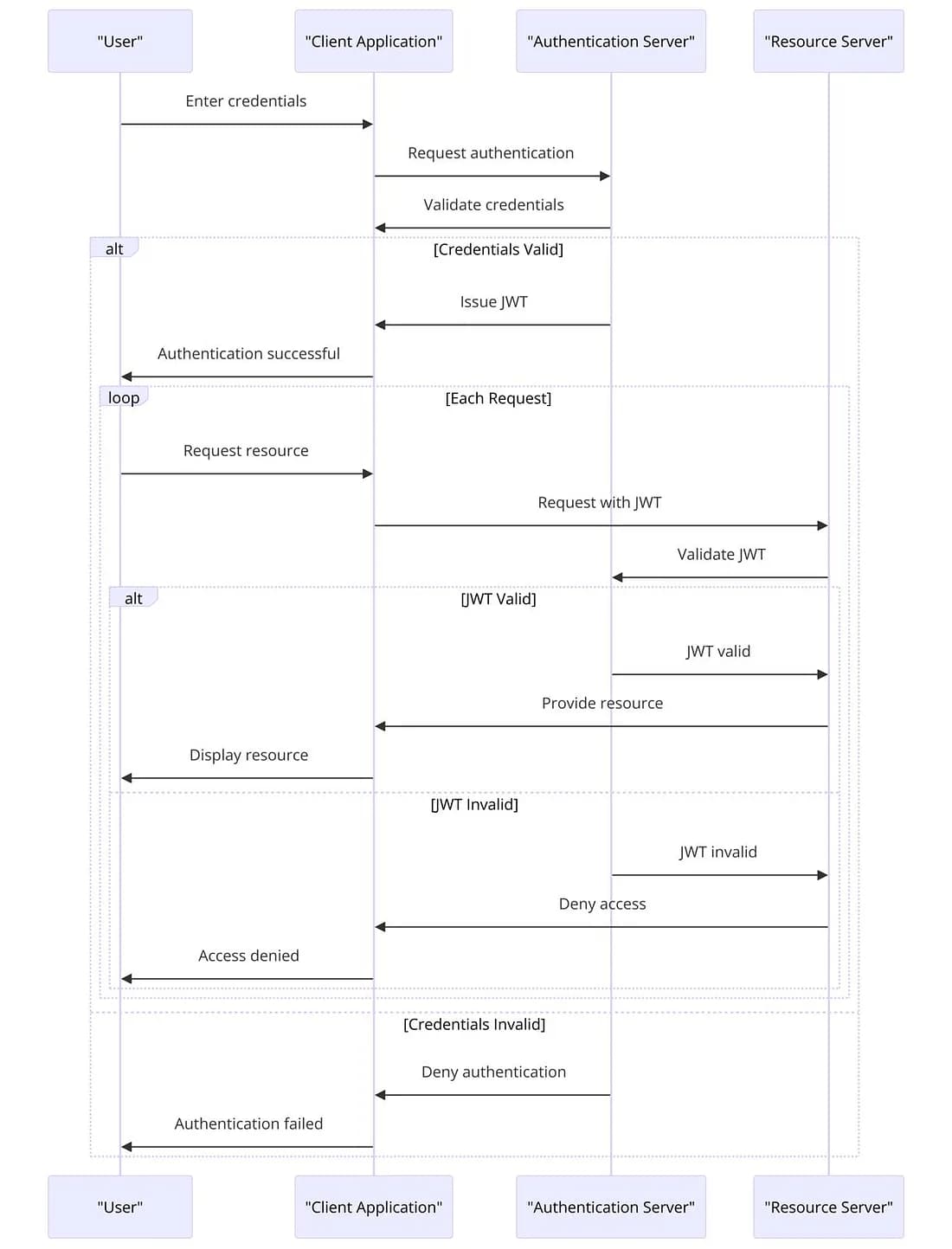

Figure 1: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token creation and validating are both handled in authentication service. For each request the microservices should ask to teh authentication service for token validation.

Figure 1: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token creation and validating are both handled in authentication service.

A Better Way of Securing a Token: Digital Signature

In modern applications, a more advanced method for securing access tokens has been developed: the use of digital signatures. This approach involves signing the token data and attaching this signature to the token. As a result, the token data itself remains transparent and accessible, but any alteration to the data will invalidate the signature. If the token contains sensitive data (which is generally not recommended), encryption can still be applied for additional security. However, using a publicly visible token secured with a digital signature offers greater flexibility for developers.

Both encryption and signing require a secret key known only to the system, ensuring that the data cannot be tampered with. However, this reliance on a single secret key introduces potential vulnerabilities in a distributed system, where the key must be shared across different system components that might be geographically separated. In the case of encryption, to decrypt the token, the secret key is needed. One solution is to always decrypt the token through a user service that possesses the key, which, however, can lead to performance issues and increased latencies. Alternatively, the key can be distributed to other services, allowing them to perform their own decryption or validation. This scenario highlights the trade-offs between security and practicality in token-based authentication systems.

This dilemma becomes evident when employing digital signatures with a single secure key for both signing and validating tokens. In microservice architectures, the most secure method for managing access tokens with digital signatures is to use a key pair, commonly referred to in cryptography as a private and public key. The token is signed with a private key, which is kept secret and known only by the user service (the token issuer). This signed token can then be verified by anyone possessing the corresponding public key, which is openly distributed. Importantly, due to the underlying mathematical and logical principles, the public key can verify a signature made with the private key but cannot be used to generate a digital signature itself. This approach effectively balances security with practicality in distributed systems.

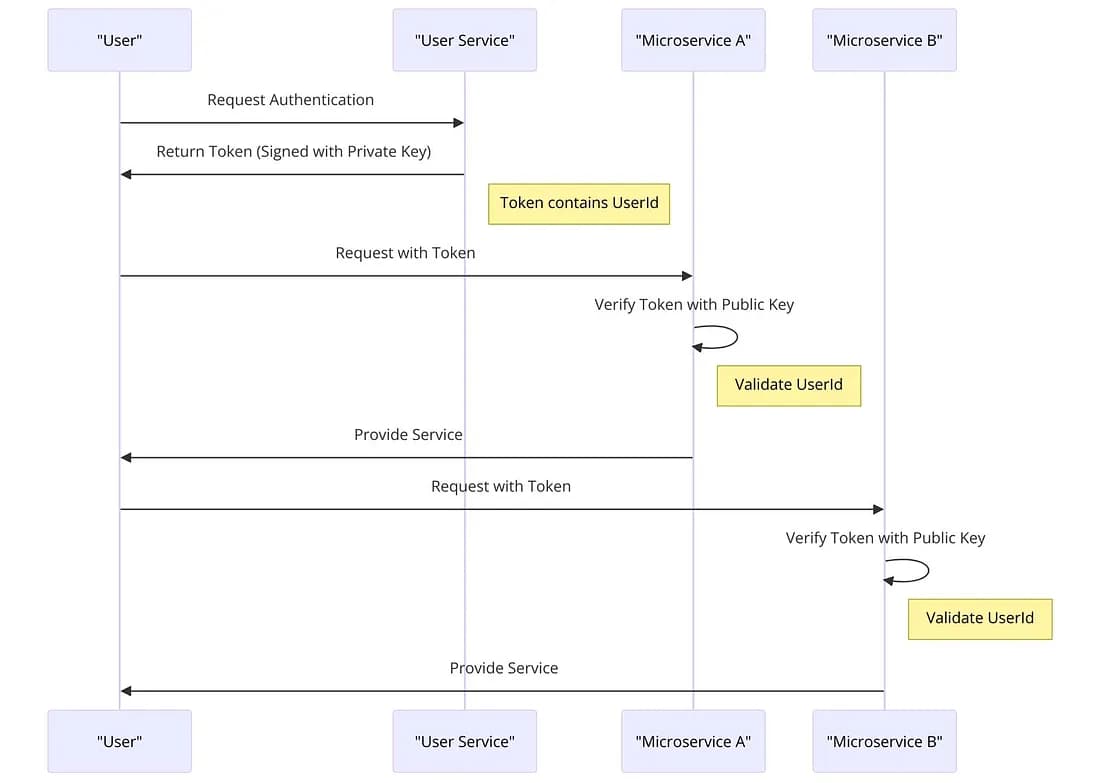

Figure 2: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token validating is handled in microservices

Figure 2: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token validating is handled in microservices with the help of the public key. Each request can be handed with in the microservices without asking the user service.

User Sessions

User sessions represent a pattern encompassing all user actions occurring between login operations. Each login initiates a new session, with the token representing this session. In certain scenarios, tokens might carry additional information about the user, such as attributes and rights. However, a prevalent practice is to maintain tokens as succinctly as possible, pairing them with a more detailed, server-side representation of the session. This leads to the concept of ‘user sessions’ — detailed data about the logged-in user stored in a server-side session store, such as a database or Redis. In a microservice architecture, positioning the session store centrally, accessible to all services, allows these services to access detailed user data without repeatedly querying the user service.

Another critical role of user sessions is in ensuring the continued validity of authenticated tokens. They act as a secondary validation mechanism to confirm that a token has not been invalidated by actions like user logout or account suspension. It’s akin to revoking the keys from someone discovered to be untrustworthy. In a microservice environment, the user service terminates the session in the store following a user’s logout or ban. This informs other services about the invalidation, preventing them from processing requests using the outdated token. User sessions, therefore, serve as an essential layer of security and data management in distributed systems.

Consuming user based attributes in a microservice environment

Once a user is authenticated, every microservice within the application is securely aware of the user’s identity, typically represented by an integer or UUID, often referred to as UserId. This UserId enables microservices to attribute user actions (or state changes) to the authenticated user. For instance, a newly created order can be marked with the UserId to denote ownership. It also allows for user-specific access control, such as displaying only the orders associated with that UserId in the order history. Additionally, the system can use the UserId to verify user permissions before allowing certain actions, like creating a product, based on the user’s assigned role.

In a monolithic application, retrieving user rights attributes such as roles or permissions is typically straightforward, often involving a simple database query. However, in a microservices environment, accessing this information becomes more complex. User access data is usually managed by dedicated services, such as a permission or authorization service, or sometimes by the user service itself. Consequently, when a client requests an action, mere authentication is not sufficient to authorize the action. An additional authorization process is required. This process, crucial for decision-making regarding user actions, presents unique challenges in a microservice-based architecture, as it involves coordination and communication across different services.

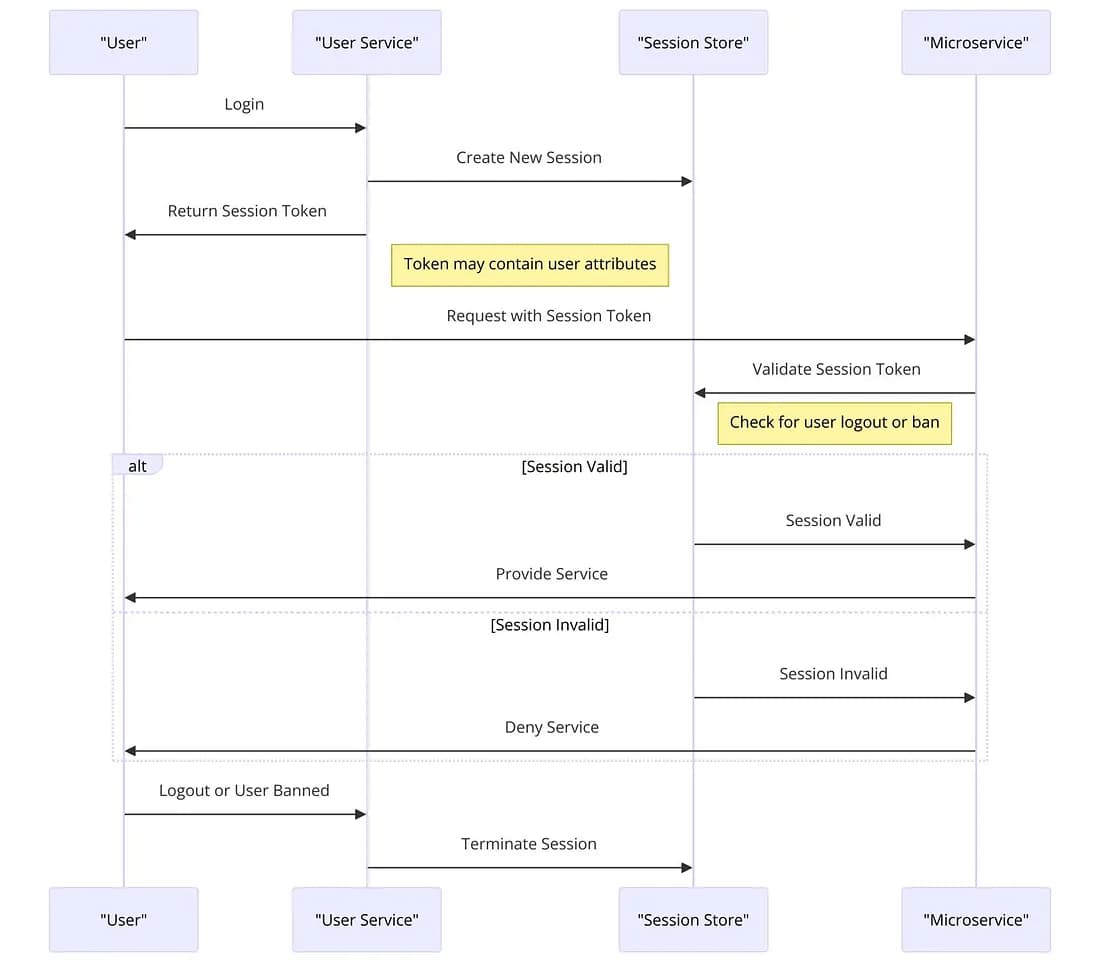

Figure 3: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token validating is handled in microservices with an additional session store check .

Figure 3: The Sequence Diagram of the scenario where the token validating is handled in microservices with an additional session store check . Session object here provides the detailed user attributes and the continuing validity of the token.

Authorization In Detail

In a microservice environment, user authorization for specific actions can follow one of two logical flows. The first involves directly querying an authorization service. This is necessary when permissions are based on complex, fine-grained logic, such as inheriting permissions from parent directories to files. In these cases, a specialized microservice handles the entire authorization logic. Each service must consult this authorization service before performing an action for a user. These authorization services should be highly performant, with a gRPC API for efficiency. Third-party tools are also available for intricate access control scenarios.

The second logical flow occurs when user authorization is based on predefined roles or specific permissions associated with certain actions. If the role and permission data for a user are manageable in size, the optimal strategy is to store this information within the session data in the session store. Thus, when a microservice needs a user’s roles or permissions, it can easily retrieve them from the session store, bypassing the need for an external authorization service. This method is suitable for complex web applications, like Amazon’s online store or Medium, where authorization mainly involves user-owned data rather than detailed roles or permissions. Here, the session store serves as an effective authorization hub for roles and permissions, unless there’s a requirement for more sophisticated authorization business logic or extensive permission datasets.

In even the most intricate of systems, user authorization often boils down to the concept of resource ownership. For platforms like Amazon or Medium, the primary concern is typically whether the user has rightful ownership or access to the resources in question — such as orders on Amazon or articles on Medium. In these scenarios, user authorization is less about the complexities of roles or permissions and more about verifying the association between the user and the resource. This means that, in many cases, simply authenticating the user’s identity — confirming they are who they claim to be — is sufficient for authorizing actions on these resources. The authenticated user ID becomes a key factor in determining whether a user should be allowed to access or modify a specific resource, streamlining the authorization process significantly in systems where resource ownership is the primary criterion for access control.

A Best Practice of User Authentication and Authorization In A Microservice Architecture

-

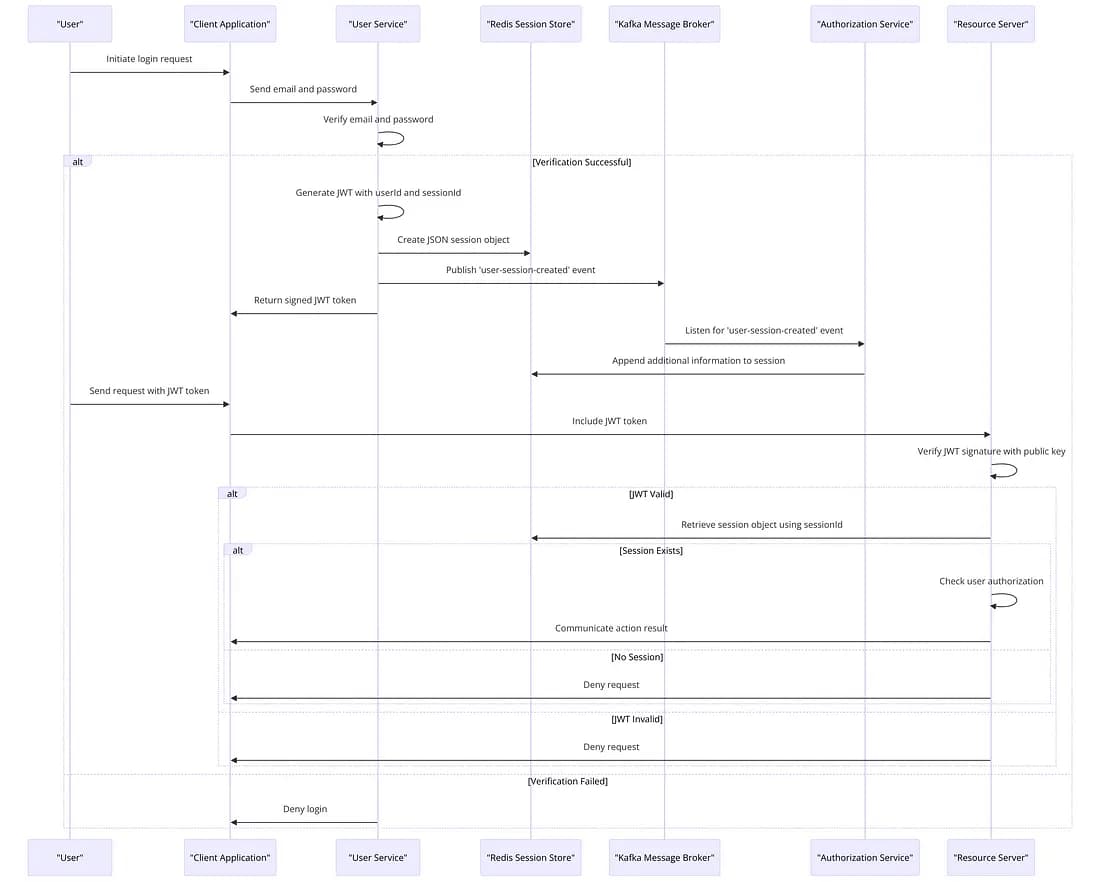

The user initiates a login request with their email and password, which is sent to the user service.

-

The user service verifies the user’s email against the database, checks the hashed password against the provided password’s hash.

-

Upon successful verification, the user service generates a JWT token, signing it with a private key securely stored on the server. This token includes the userId and a randomly generated sessionId.

-

The user service then creates a new JSON session object in the Redis session store, containing all relevant user data along with the userId and sessionId.

-

A ‘user-session-created’ event is published by the user service to the Kafka message broker.

-

The user service returns the signed JWT token to the client, either within a cookie or in the response body.

-

The authorization service listens for the ‘user-session-created’ event, and appends to the user’s session additional information such as roles, purchased upgrades, or specific permissions, if defined.

-

The user sends a subsequent request to a resource server (like an article server to start a new article), including the signed JWT token.

-

The resource service verifies the JWT token’s signature using the user service’s public key, which is accessible to all services.

-

Once authenticated, the service acknowledges the userId as representing the user. Using the sessionId from the token, it retrieves the session object, which includes detailed user information, from the session store. If no corresponding session object exists, the request is denied.

-

With access to the session data, the resource server checks the user’s authorization for the specific action (e.g., verifying premium user status for article creation) and performs the necessary actions on the resources it manages.

-

The resource service then communicates the result of the action back to the user.

Figure 4 :The Detailed Sequence Diagram of the best authentication and authorization practice.

Figure 4: The Detailed Sequence Diagram of the best authentication and authorization practice. Digitally signed JWT Tokens are used for authentication with paired keys and session object provides the continuing validity of the token with detailed user attributes and user rights to authorize the user for specific user actions.